by Alan Stein Jr

My #1 priority is to be a present, loving, and supportive father to Luke, Jack, and Lyla. My primary responsibility is to raise well-adjusted, self-aware, and confident children that grow up to have high character and integrity, and who have developed the skill sets necessary to make a positive contribution to the world.

I know that sports are an invaluable tool in accomplishing this. At the most fundamental level, sports should be fun platform to teach children values like teamwork, work ethic, accountability, respect, character, selflessness, loyalty, sportsmanship, leadership, competitiveness, how to deal with adversity, and how to earn success. But the key to doing that is making sure they have fun and enjoy the experience.

At the youth level, which I will define as elementary and middle school age, winning should not be the primary goal and should not be heavily emphasized. The focus should be on having fun, developing movement and technical skills, as well as learning how to be a good teammate, to be coachable, and how to play the game the right way. But you can do all that and still keep score!

It’s okay to have winners and losers. Not keeping score is a futile attempt to coddle our children and keep them insulated in a bubble. This will end up backfiring as we create an epidemic of entitled children whose self-esteem has been built on a house of cards. Kids need to learn how to win graciously and lose gracefully. As someone much wiser than me has said, “We need to prepare our children for the path, not prepare the path for our children.” But just because you keep score, doesn’t mean you have to emphasize winning. They are not the same thing. As adults, we need to praise and reward the process, not the outcome. Praise the effort, not the score. Praise the improvement, not the win/loss record.

At the youth level, everything that is done to increase the chance of winning decreases the overall development and enjoyment of the game for the kids involved.

When you emphasize winning:

- you create an environment where kids fear making mistakes. But mistakes are the primary ingredient of growth and development!

- you reward the more mature and advanced kids and leave the others behind.

- you teach kids that the outcome is more important than the process. That is a very dangerous mindset to instill if your goal is to raise happy and successful children.

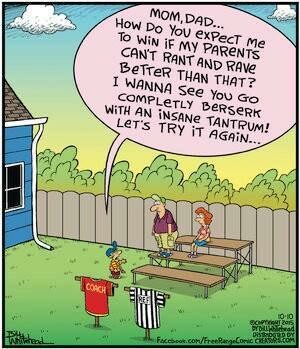

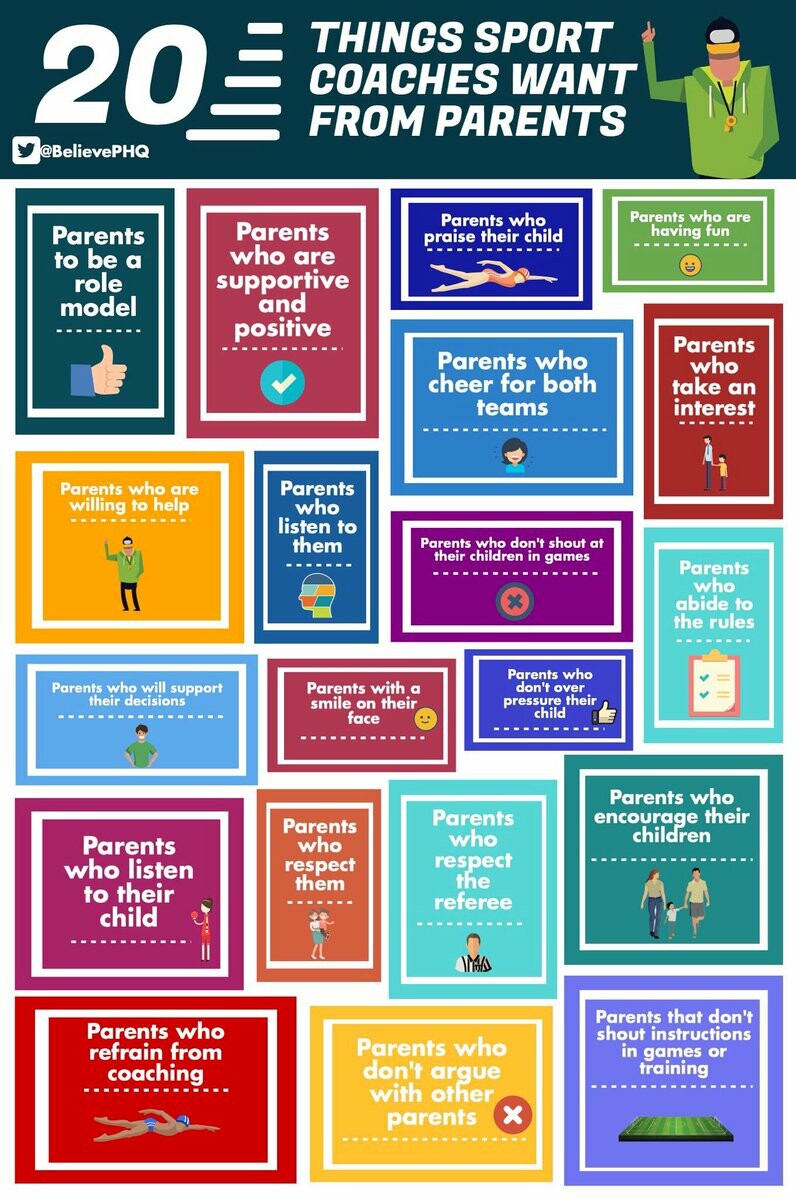

I want to respectfully address parents that shout instructions to their child from the sideline. While I know this is well intended, it stunts development and makes the game a lot less fun for the kids. As parents, we should be cheering, encouraging and supporting our little rascals, and offering praise when appropriate. Screaming ‘shoot’ or ‘pass’ at the top of your lungs does not add value nor does it help. In fact, it adds pressure, confusion, and robs the child of arguably the most important skill set in sports – the ability to make decisions. From a fundamental standpoint, shooting the ball should be an action, not a reaction! Lastly, it undermines the coach.

Our children should only receive instruction from one person during a competition – their coach.

As youth parents and coaches we should all be emphasizing fun and development and praising great attitudes and work ethics, not berating referees, anointing National Champions and creating a win-at-all-costs, high-pressure environment. So, how do we do that? What are some tips to doing youth sports right? Research has shown that the best phrase you can say to your child after a practice or game is:

"I love to watch you play!"

That’s it.

That statement has been a game changer for me (pun intended). I have programmed myself to say that to my kids every time. And without fail, their faces light up with a big smile when I do. Please try it.

Another recommendation is for you to offer your kids these 4 reminders before every practice and every game:

- Have fun

- Play hard

- Listen to your coach

- Be a good teammate

If they can do those 4 things every time they take the court or field, then they will be getting the full benefit that sports offer at such an impressionable age. I also want to recommend you encourage your children to stay involved in as many sports as they can for as long as they can. Both individual sports like golf, tennis and martial arts, and team sports like basketball, baseball and soccer, is healthy for them mentally and physically. It will give them time to find what they are good at and what they are most passionate about.

Early sport-specialization is the wrong move. Trust me. Encouraging your children to play multiple sports in elementary and middle school will in no way limit their ability for future success in one particular sport. Believing that a child needs to play one sport, only one sport, year-round beginning at age 8 or 9, is a dangerous trend that is completely misguided. Playing multiple sports throughout the year has numerous benefits. The primary one is it helps alleviate burnout and overuse injuries.

This trend started when parents (unintentionally) began bastardizing the ‘10,000 Rule’ by Malcolm Gladwell (which states it takes approximately 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to master a skill). This has two glaring errors. One, the study he referenced was with musicians (pianists), not athletes. There is a huge difference in the physical toll taken on a child’s body between playing the piano and playing competitive basketball (for example). And two, the key is DELIBERATE practice.

“Deliberate practice refers to a special type of practice that is purposeful and systematic. While regular practice might include mindless repetitions, deliberate practice requires focused attention and is conducted with the specific goal of improving performance.” – James Clear

So simply having a child ‘play 10,000 hours of basketball from age 8 to 18’ is NOT what Gladwell intended. Logging hours is not the answer. All training needs to be intentional, purposeful, and deliberate. Having been involved in elite basketball my entire life – I can promise you that 95% of what is currently going on at youth practices and training sessions is not deliberate practice.

On an unrelated, but equally important topic, the concept of ‘everyone-gets-a-trophy’ to raise children’s self-esteem does not work. It provides a false sense of accomplishment, entitlement, and creates fragile egos.

By definition, it’s not an accomplishment unless it is earned.

For me personally, as a father, I do not let my children beat me in any games of skill, strength or speed. No, I am not a sociopath. I do this to teach them about life. When I win, I teach them the importance of losing with class and grace. In games of skill, strength or speed, I will often handicap the rules (EX: give them a significant head start in a race) to give them better odds. However, I still do my best to beat them. In many instances, with the right handicap, they will win. When they do, I congratulate them and tell them how proud I am of their effort, I recognize how hard they worked, how much they practiced, and how they never quit. I make sure to acknowledge the process, not the outcome. I don’t make a big deal when they win/lose, but rather highlight the role their effort and attitude played.

Most importantly, I always model the appropriate behavior whether I win or lose. I am confident that my stance will teach my children to respect the process, embrace practice, always give a great effort, earn everything in their life, and handle both winning and losing with class.

And THAT is the key to being happy, fulfilled, and successful!

Let’s work together to protect the sanctity of youth sports and raise our kids to add real value to the world.