How the pressure of perfectionism can be alleviated by coaching strategies that focus on effort not execution, beliefs and behavior

by Bo Hanson

‘The Rise of Perfectionism’ among college students is a significant trend according to an article by the Harvard Business Review. In summary, the article was reporting on research conducted by the World Health Organization (WHO), which surveyed 41,641 American, Canadian, and British college students from 1989 to 2016 and found an increasing tendency towards perfectionism – unrealistically high expectations of achievement.

Most profound and concerning was the WHO’s finding that the expectations society puts on individuals have doubled, when compared with the expectations placed on individuals by themselves and by others. This means the environment created by society is developing unhealthy behaviors in our young people.

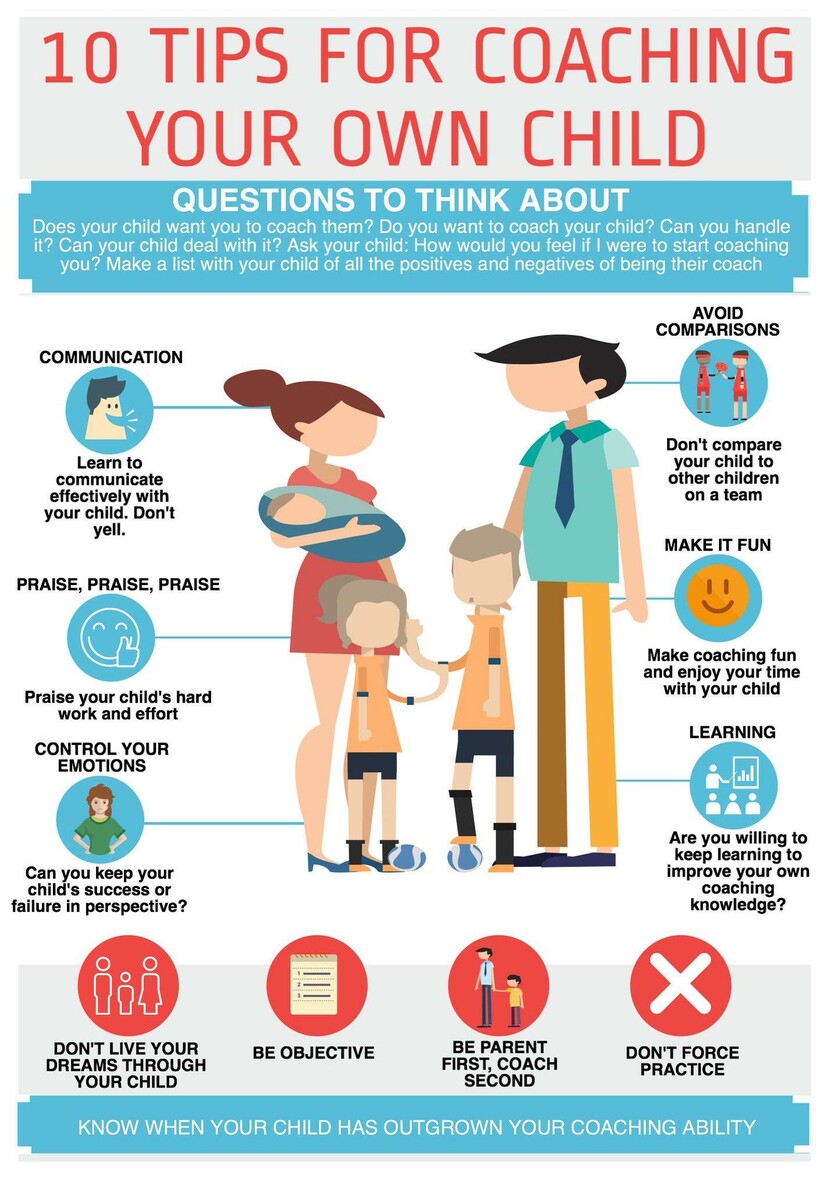

The article caused me to reflect on the role that coaches, as figures of influence in young people’s lives and people whose primary role is to create a healthy environment, play in creating realistic expectations. A coach can create a culture that supports growth not unrealistic achievement and perfectionism. Or, and this may be controversial, a coach can also create the expectation that their athletes must perform at their ‘best’ every time. Being ‘your best’ every time is also an example of being perfectionistic and unrealistic. As well, defining what being at your best means is critical. Is it ‘giving best effort’ or ‘technically being mistake free’?

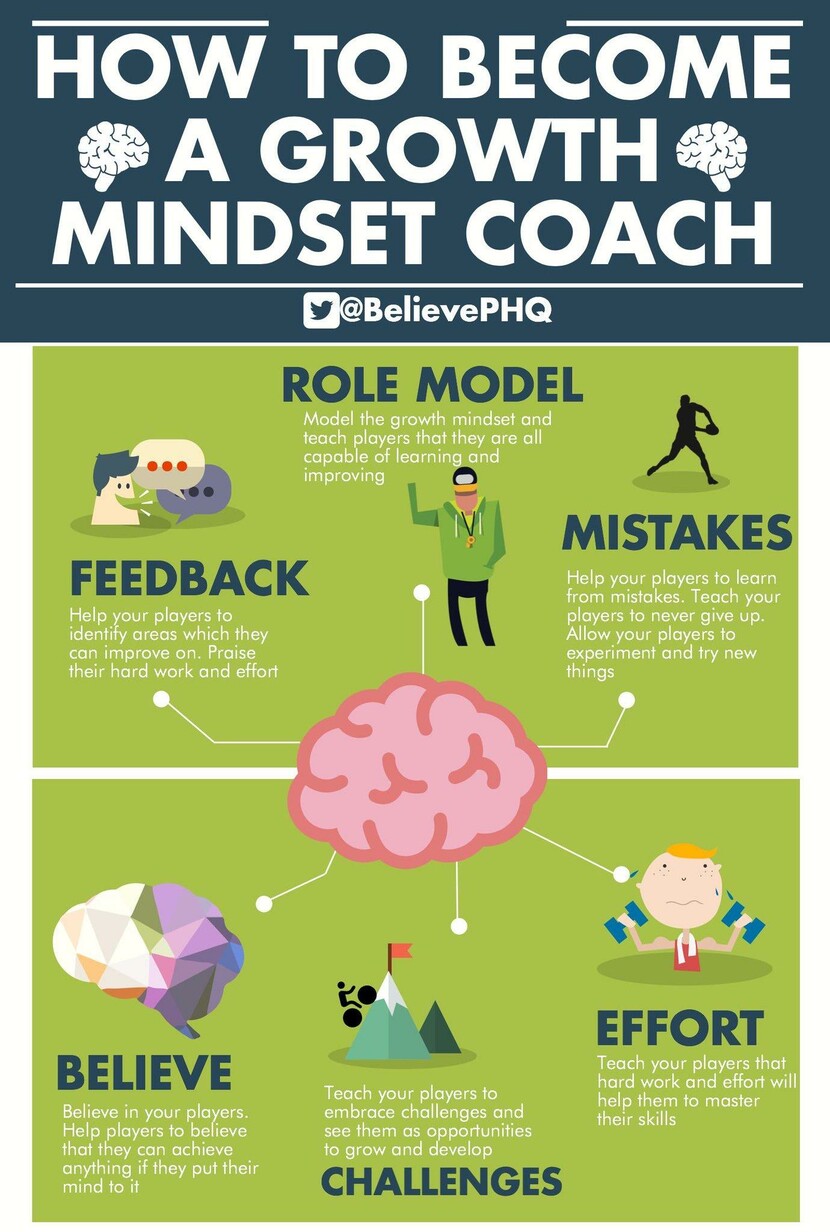

In this article we’ll examine where perfectionism comes from and explore some strategies to ensure your program gets results and supports athletes as people. We look at ways a coach can give feedback to encourage improvement, as opposed to focusing on short-term outcomes, the role of beliefs and how to establish an effective system of self-review. Plus, we look at intrinsic motivation and how it inherently combats the pressure of unrealistic expectation.

Focus on Effort NOT Execution

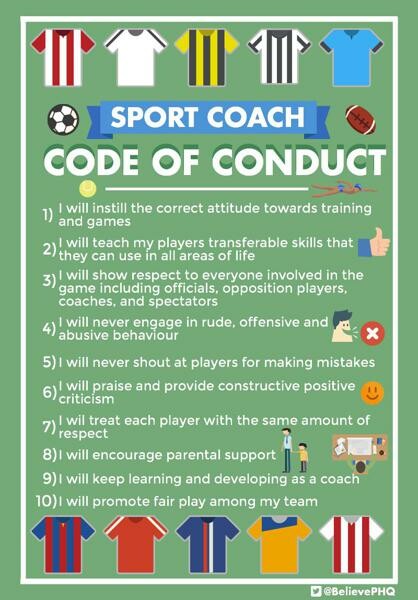

To jump straight in, coaches who get their culture right talk about effort not execution. They talk about commitment not compliance and they talk about being better not being perfect.

Saying to an athlete, ‘your effort during practice today was outstanding and this was the contributing factor to the great results you achieved for the team’, is very different and far more conducive to improvement than saying, ‘you did a wonderful job today. You’re such a talented player.’

The first round of feedback focuses on effort, the coach’s attention and words are rewarding the athlete for trying hard and applying themselves, the second comment does not encourage effort at all, rather, it’s about execution. Effort is the major aspect of any process.

A coach’s feedback is always important, but when an athlete makes a mistake it’s even more important! If an athlete has perfectionistic expectations of their performance and makes a mistake or falls short of their own standards (which they will), they can focus on the mistake rather than recovering and the negative self-talk is damaging for their self-belief and it can cause them to miss the next moment or the next play. They begin a downward spiral, not recovering.

The WHO identifies that socially prescribed perfectionism also has the most significant association with mental health problems like depression and anxiety.

When an athlete makes a mistake, it’s important that coaches recognize the athlete’s effort and give corrective instruction on what to do right next time. Thus, feedback must be focused on only what the athlete can control (process) and not the outcome. It’s imperative to give athletes a process for improving their performance – a how-to guide. Punishment based on execution will lead to an unhealthy fear of failure which is the kind of mindset we are trying to avoid. Focus on the pure technical or effort element to improve. Also, choose to focus on competing. All athletes make mistakes and competing is about recovering from these errors faster than the opposition.

In addition to recognizing effort, knowing what attributes individual athletes are working on, can help a coach give direct and encouraging feedback. These non-technical focus areas are the key to avoiding an overemphasis on outcomes and performance. They may also be a resource for coaches when performance outcomes are less than ideal. Non-technical elements include giving direction, being the energy in the team, etc.

Empowering Through Behavior

It’s worthwhile to backtrack here to explain that AthleteDISC Profiles empower the athlete and the coach with knowledge about an athlete’s behavioral strengths and areas to work on. Athletes can use this knowledge as a basis to build their list of behaviors they are working on. These behaviors can be assembled and assessed in a self-review. We call this exercise in self-review a Behavioral Scorecard and this can form a part of an athlete’s non-technical focus or role on the team.

Typically, behavioral attributes lead to performance attributes. Some examples of behavioral attributes are; integrity, respect, honesty, compassion and determination, while performance behaviors may include focus, confidence, competitiveness, self-discipline and mental toughness.

With the Behavioral Scorecard, each individual identifies five strengths (Natural Behaviors in their AthleteDISC Profile) that come easily to them and also five areas they need to consciously work on (Adapted Behaviors). They use their DISC Profile report as a tangible way to identify these. Then, on a weekly basis, they score themselves based on how they are performing.

Where they give themselves a low score, they then work on this to improve. The approach is to develop their ‘behavioral muscle’. This requires practice and conscious attention, in the same way we would develop any muscle. We need to exercise it regularly and consistently to become stronger and to be able to rely on it when the pressure is on.

Our focus is on behavior as it is something that’s adaptable and controllable.

Where behaviors are displayed at the highest level and execution is not 100%, then there is room for technical skill development which is what practice is about. When behavior is poor there exists a far greater problem.

Obviously, in high-performance sport, technical execution and high-level personal behaviors have to be present. When everyone does both of these consistently, then teams produce winning results. Another vital piece of the performance equation is the impact of an athlete and coach’s beliefs.

Impact of Beliefs

Beliefs are fundamental programs (like a computer program – and we have all been programmed in some way) which create a ‘map’ of how to navigate through life. A belief is also something we have absolute certainty about. Beliefs are not necessarily true or false, but are simply what you choose to believe about something. Beliefs can and are about all things… we have thousands of beliefs. Some beliefs however are more significant than others. Athletes have beliefs about their sport.

For example, their ability to play well or what the cause of a good performance is. If they say, ‘I practiced so well this week and played well in the game’ they are giving you their belief that great practice equals or leads to great game play. This is neither true or false. It may, for some, but not for others. The most critical aspect of a belief is if it is helping or hurting your performance. Coaches have a responsibility to ensure their athletes’ beliefs are helping them and not hurting their performance.

The belief that one has to be perfect is an example of a belief which does not help.

The WHO’s research concluded that, “the energy behind perfectionism comes largely from a desire to avoid failure”. Wanting to avoid failure is normal and usually pushes us to prepare and focus. However, if failure can only be avoided by being perfect, making no mistakes, then this unrealistic expectation will dramatically hinder performance. Often athletes become hyper-aware and over analyze their movement execution in the hope this will help them. It never works.

Again, these are all examples of beliefs athletes have which are not helping them.

Coaches need to be involved in this mental landscape, because previous generations had the opportunity to learn mental skills from their environment, comparatively, Millennials live in a world which is more heavily managed, and risk averse until parents wanting to shelter their children from negative or challenging experiences. Coaches have to become teachers of critical life and mental skills. Skills which the environment has not taught this generation through exposure or non-scrutinized errors and expectations from ‘too well meaning’ parents and Coaches.

Critical life skills like resilience, communication, leadership, team work, goal setting and decision making can become measurables and success in these areas can give rise to intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivators or internal motivation can’t be denied. Compared to extrinsic motivators like the media’s regards, payment for achievement or hierarchical promotion.

Some examples of intrinsic motivators are the quality of their effort and energy, whether they lived the team’s values, whether they performed in line with the behavioral qualities that make them proud of and whether they experienced personal growth. The feeling and belief that we are growing is an incredible intrinsic motivator. As well, most athletes know that growth is more likely to happen when we feel ‘allowed’ to make mistakes through trial and error.

When athletes do this, they experience strong personal fulfillment and pride in themselves that cannot be taken from them by an external observer’s comments such as media or others outside of the team or even the scoreboard itself. Meeting their own personal intrinsic motivators energizes an athlete to further commit themselves to give full EFFORT.

A belief that I’ve seen work very well is that:

There are no failures, only outcomes—as long as I learn something I’m succeeding.